Spinal Stress Fractures: Maintaining Suspicion

Video here or blog below

Introduction

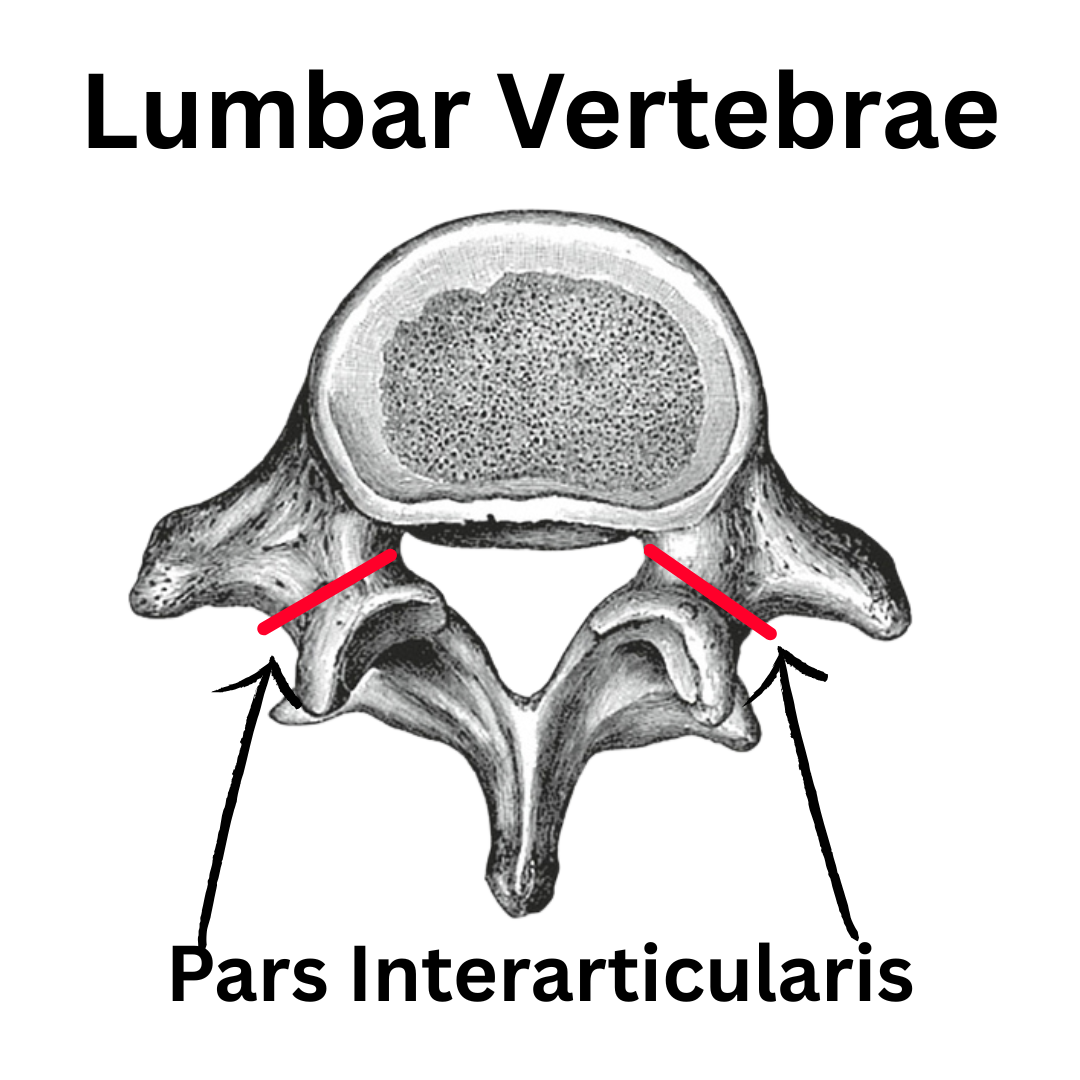

Lumbar spinal stress fractures, often termed pars defects or spondylolysis, are common in adolescent athletic patients with low back pain.

Spondylolysis is often under-recognised in younger athletes.

Early identification and appropriate management are essential to prevent progression to more significant structural changes, such as spondylolisthesis.

The earlier you catch it the quicker it will heal

Risk Factors

A stress fracture of the pars interarticularis develops when repetitive loading exceeds the bone’s capacity for repair. In the lumbar spine, this typically occurs at the L5 level, followed by L4 (Standaert & Herring, 2000).

Key risk factors include:

- Repetitive extension and rotation movements (e.g., gymnastics, cricket fast bowling, diving, weightlifting) (Campbell et al., 2016).

- Adolescent athletes undergoing rapid growth, where the pars may be biomechanically vulnerable.

- Training load errors, particularly increases in intensity, frequency, or technique-related stressors.

- Biomechanical factors, such as increased lumbar lordosis or reduced hip mobility, leading to compensatory extension stresses.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with spinal stress fractures often report:

- Focal low back pain, sometimes unilateral, that worsens with activity and eases with rest.

- Pain provoked by extension-based movements (standing, arching, sporting skills such as bowling or jumping).

- Minimal or no leg symptoms in early stages, differentiating it from disc pathology.

- Tenderness over the lumbar spine, sometimes localised to the pars region.

Some people may use the single-leg hyperextension test, but the sensitivity and specificity are limited (Masci et al., 2006). I don’t use this test.

Imaging Considerations

- MRI is preferred in early cases, as it can detect bone stress reactions before fracture develops (Campbell et al., 2016).

Management Principles

Management strategies emphasise load modification, rehabilitation, and gradual return to sport.

Acute Phase

- Relative rest: Avoid activities that reproduce pain, particularly extension and rotation. Absolute rest is rarely indicated but symptom-guided modification is essential.

- Bracing: Evidence for routine bracing is mixed, with recent literature suggesting no significant long-term benefit over activity modification alone (Standaert & Herring, 2000; Campbell et al., 2016).

Rehabilitation Phase

- Core stabilisation: Emphasis on deep trunk control (transversus abdominis, multifidus) to support spinal stability.

- Hip and thoracic mobility: Reducing compensatory lumbar extension by optimising movement elsewhere.

- Progressive strengthening: Gradual reintroduction of functional and sport-specific loading, ensuring pain-free progression.

Return-to-Sport Phase

- Graded exposure to sport-specific movements, ensuring:

- Pain-free spinal extension under load.

- Adequate neuromuscular control.

- Monitoring of workload and recovery strategies.

Return timelines vary but often range from 3–6 months, depending on severity, healing, and sport demands (Cain et al., 2015).

Prognosis and Long-Term Considerations

Most athletes return to full sport following structured rehabilitation. However, some may experience:

- Persistent symptoms if diagnosis is delayed.

- Risk of progression to spondylolisthesis if bilateral defects occur.

- Psychological impacts of enforced rest and rehabilitation, requiring ongoing support.

Final Thoughts

- Maintain suspicion: Particularly in young athletes with extension-related low back pain.

- Use clinical reasoning: Combine history, movement provocation, and physical exam to guide referral.

- Educate athletes and parents: Emphasise the importance of respecting pain and gradual recovery.

- Collaborate: Work closely with sports coaches and medical teams to optimise load management.

- Think long term: Address biomechanics, training habits, and recovery to reduce recurrence risk.

References

Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG. (2016). Imaging of pars interarticularis defects. Clinical Radiology, 71(2): 106–118.

Cain TE, Dugas JR, Wolf RS, Andrews JR. (2015). Classification and treatment of stress fractures. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 34(2): 231–238.

Masci L, Pike J, Malara F, Phillips B, Bennell K, Brukner P. (2006). Use of the one-legged hyperextension test and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active spondylolysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(11): 940–946.

Standaert CJ, Herring SA. (2000). Spondylolysis: a critical review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(6): 415–422.